Flow Matching (Part 1)

This is the beginning in a series of blog posts about flow matching and its generalizations. We start by covering normalizing flows, the foundation for flow matching methods.

Introduction

This is part one in a series of blog posts that will provide an introduction to flow-based models and flow matching.

Flow-based models are an example of a probabilistic generative model. The goal of probabilistic modeling is to model the distribution of a random variable \(X\). This is typically done in a supervised fashion using examples \(\{x^{(i)}\}_{i=1}^N\) collected from the data distribution. We learn to approximate the probability density function of the data distribution with a model \(p(x;\theta)\) where \(\theta\) represents the parameters of a neural network. Why might this be useful? The most well-known use case is sampling. Once we have an approximation of the data distribution, we can sample from it to create new unseen data. In the past decade, we have witnessed Variational Auto-Encoders (VAE), Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN), and diffusion models at the forefront of research in generative modelling

Although flow-based models have recieved relatively less attention compared to other generative models in those years, there has been a recent surge in popularity due to the advent of flow matching. Flow matching encompasses diffusion models as a special case and offers a more simple and flexible training framework. We will build up to flow matching by covering some of the other relevant techniques developed for flow-based modeling in the past decade. Part one will start with normalizing flows and cover residual flow methods. Part two will touch on Neural ODEs and dicuss continuous normalizing flows. Finally, in part three, we dicuss flow matching and its generalizations such as Riemannian flow matching.

Other than being a competitive alternative to diffusion models, what are some other motivations to study flow-based methods and flow matching? Well, flow-based methods are capable of likelihood evaluation because they model the probability density function directly. Also, as we will see, the flow matching framework relies on Ordinary Differential Equations (ODE) so they are more effecient at sample generation compared to diffusion models.

Change of variables

In future blog posts, we will see that flow matching is a way to train continuous normalizing flows. So we start by covering the basics of normalizing flows. The framework for normalizing flows is based on a rather simple fact from probability theory

The notation \(\frac{\partial f^{-1}}{\partial \mathbf{x_1}}\) denotes the Jacobian of \(f^{-1}\). Also, because the transformation is invertible, we can write \(p\) in terms of \(q\) too:

\[\begin{align*} p(\mathbf{x_0}) &= q(\mathbf{x_1})\left|\det \frac{\partial f}{\partial \mathbf{x_0}}(\mathbf{x_0}) \right| \\ &= q(f(\mathbf{x_0}))\left|\det \frac{\partial f}{\partial \mathbf{x_0}}(\mathbf{x_0}) \right|. \end{align*}\]Example 1 . Scaling and shifting a Gaussian. Suppose \(\mathbf{x_0} \in \mathbb{R}\) and \(\mathbf{x_0} \sim \mathcal{N}(0,1)\). Let \(\mathbf{x_1} = f(\mathbf{x_0}) = \sigma \mathbf{x_0} + \mathbf{\mu}\). Then \(\mathbf{x_0} = f^{-1}(\mathbf{x_1}) = \frac{\mathbf{x_1} - \mathbf{\mu}}{\sigma}\) so \(\frac{df^{-1}}{d\mathbf{x_1}} = \frac{1}{\sigma}\). In this case, the Jacobian is a positive scalar function so the determinant is itself. Recall the pdf of a canonical Gaussian:

\[p(\mathbf{x_0}) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}}e^{-\frac{1}{2}\mathbf{x_0}^2}.\]Applying the formula we obtain a Gaussian with mean \(\mu\) and variance \(\sigma^2\),

\[\begin{align*} q(\mathbf{x_1}) &= p\left(f^{-1}(\mathbf{x_1})\right)\left|\det \frac{\partial f^{-1}}{\partial \mathbf{x_1}}(\mathbf{x_1})\right| \\ &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}}e^{-\frac{1}{2}(\frac{x - \mathbf{\mu}}{\sigma})^2}\frac{1}{\sigma} \\ &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma}}e^\frac{-(x-\mathbf{\mu})^2}{2\sigma^2}. \end{align*}\]Intuitively, multiplying \(\mathbf{x_0}\) by \(\sigma\) stretches the domain which changes the variance of the Gaussian. Adding \(\mu\) applies a shift to this stretched Gaussian.

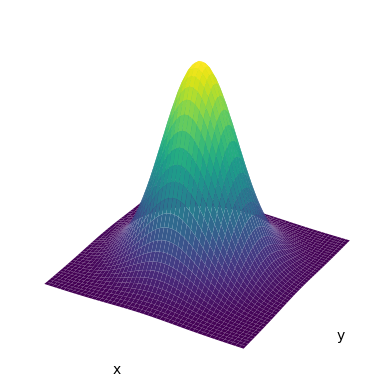

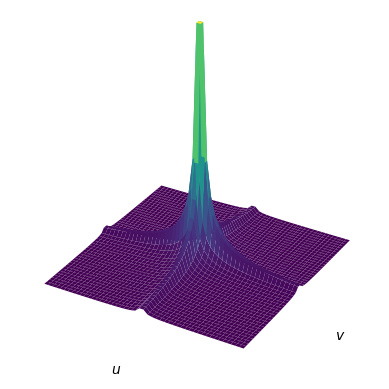

Example 2 . Non-linear transformation of a canonical Gaussian. Suppose \(\begin{bmatrix} x \\ y\end{bmatrix} \sim \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{0}, \mathbf{I})\). The pdf of a canonical Gaussian in 2D is:

\[p(x,y) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}}e^\frac{-(x^2 + y^2)}{2}.\]Let’s apply a cubic transformation to each coordinate, \(u = x^3\) and \(v = y^3\). The inverse is \(x = u^\frac{1}{3}\) and \(y = v^\frac{1}{3}\). The Jacobian of this transformation is the following:

\[\begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial x}{\partial u} & \frac{\partial v}{\partial v} \\ \frac{\partial y}{\partial u} & \frac{\partial v}{\partial v} \\ \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{3}u^{-\frac{2}{3}} & 0 \\ 0 & \frac{1}{3}v^{-\frac{2}{3}}\\ \end{bmatrix}.\]The absolute value of the determinant of this matrix is \(\frac{1}{9}\lvert uv\rvert ^{-\frac{2}{3}}\). Therefore,

\[\begin{align*} q(u, v) &= \frac{1}{9}\lvert uv\rvert ^{-\frac{2}{3}} p(x,y) \\ &= \frac{1}{9}\lvert uv\rvert ^{-\frac{2}{3}}p(u^\frac{1}{3}, v^\frac{1}{3}) \\ &= \frac{\lvert uv\rvert ^{-\frac{2}{3}}}{9\sqrt{2\pi}}e^\frac{-(u^\frac{2}{3} + v^\frac{2}{3})}{2} \\ \end{align*}\]

Normalizing flows

In the next sections, we will see that flow matching is capable of transforming between arbitrary distributions \(p\) and \(q\). But in the context of normalizing flows for generative modeling, \(p\) is simple distribution which we can sample from easily, typically a canonical Gaussian and \(q\) is our data distribution which we only have samples from i.e. the dataset \(x^{(i)}\). Our goal with this setup is to learn the transformation from \(p\) to the complex data distribution \(q\). We can do this by learning the invertible transformation \(f\). The function \(f\) will involve the use a neural network with parameters \(\theta\), so from now on we will denote the transformation as \(f_\theta\). Once we have learned \(f_\theta\) we will have access to \(\hat{q}\) which hopefully will be a good approximation of \(q\).

Given that we learned \(f_\theta\), how do we do density estimation and generate samples from \(q\)? This is quite simple for flow models. If you have a data sample \(\mathbf{x}^{(i)}\), you can compute \(f^{-1}(\mathbf{x}^{(i)})\) and the deterimant of the Jacobian. Then plug those into eq. (1) to obtain \(\hat{q}(\mathbf{x}^{(i)})\). If you want to sample from \(q\), first obtain a sample \(\mathbf{x_0} \sim p\) which we know how to do because \(p\) is a simple distribution. Then, we can compute \({\mathbf{x_1} = f^{-1}_\theta(\mathbf{x_0})}\) and so \(\mathbf{x_1}\) will be a sample from \(\hat{q}\). Essentially, normalizing flows provide a way to learn how to transform samples from a simple distribution to a complex data distribution. This might seem a bit neboulous right now. How do we learn the transformation \(f_\theta\) using only samples from the complex data distribution? First, we have to discuss how to determine the design of \(f_\theta\) and ensure that it is invertible.

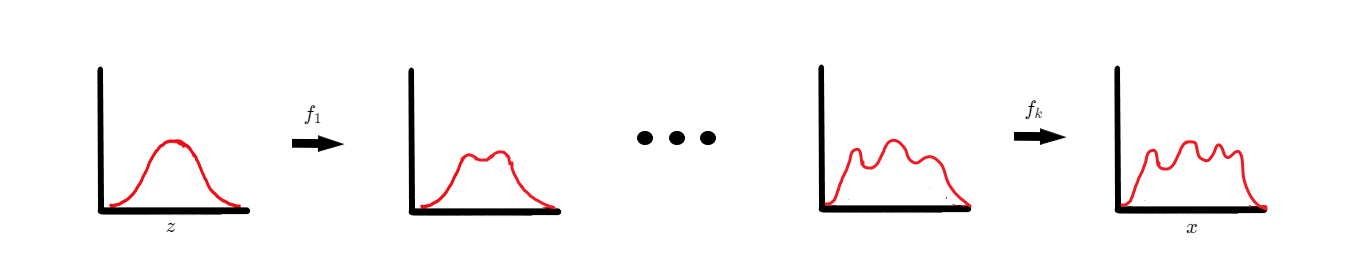

Ensuring invertibility is challenging so normalizing flow methods start with imposing a specific structure on \(f_\theta\). We want to learn the transformation from \(p\) to \(q\) as a sequence of simpler transformations. Define functions \(f_1 \cdots f_k\) to be invertible and differentiable. Note these functions are still parameterized by \(\theta\) but we omit making this explicit for sake of notation. Invertible and differentiable functions are closed under composition. We can use this fact to define \(f_\theta\) in the following manner:

\[f_\theta = f_k \circ f_{k-1} \cdots f_2 \circ f_1.\]The intiution behind this formulation is somewhat analagous to the justification of stacking many layers in a deep learning model instead of using one wide layer. Learning the transformation from \(p\) to \(q\) in one step might be too difficult. Instead, we can learn a sequence of functions where each function is responsible for transforming its input distribution into a slightly more complex distribution. Eventually, over the entire sequence we are able to model the complexity of the data distribution. Furthermore, now we only need to ensure that each simpler transformation is invertible which should be easier than designing a complex invertible transformation in one step.

Let’s reformulate the process of normalizing flows. Since we are performing multiple steps, \(\mathbf{x_1}\) is no longer a sample from \(q\) but a sample from a distribution slightly more complex than \(p_0 = p\). After applying \(K\) transformations we will have that \(\mathbf{x_K} \sim \hat{q}\):

\[\begin{align*} &\phantom{\Rightarrow} \ \ \mathbf{x_0} \sim p_0, \quad \mathbf{x_1} = f_1(\mathbf{x_0}) \\ &\Rightarrow \mathbf{x_1} \sim p_1, \quad \mathbf{x_2} = f_2(\mathbf{x_1}) \\ \phantom{\Rightarrow x_1} &\cdots \\ &\Rightarrow \mathbf{x}_{K-1} \sim p_{K-1}, \quad \mathbf{x}_K = f_K(\mathbf{x}_{K-1}) \\ &\Rightarrow \mathbf{x}_K \sim p_K = \hat{q} \approx q. \end{align*}\]The sequence of transformations from \(p\) to the distribution \(q\) is called a flow. The term normalizing in normalizing flow refers to the fact that after a transformation is applied, the resulting pdf is valid i.e. it integrates to one over its support and is greater than zero.

So how do we actually train normalizing flows? The objective function is simply the maximum log-likelihood of the data:

\[\begin{align*} \theta^* &= \max_{\theta} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \log(\hat{q}(\mathbf{x}^{(i)})) \\ &= \max_{\theta} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \log\left(p\left(f^{-1}_\theta(\mathbf{x}^{(i)})\right)\left|\det \frac{\partial f^{-1}_\theta}{\partial \mathbf{x}_K}(\mathbf{x}^{(i)})\right|\right) \\ &= \max_{\theta} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \log p\left(f^{-1}_\theta(\mathbf{x}^{(i)})\right) + \log\left|\det \frac{\partial f^{-1}_\theta}{\partial \mathbf{x}_K}(\mathbf{x}^{(i)})\right| \end{align*}.\]Remember that \(f_\theta\) is actually the composition of a sequence of functions. We can simplify the determinant of the Jacobian of \(f\) by decomposing it as a product of the individual determinants. Specifically,

\[\left| \det \frac{f^{-1}_\theta}{\partial \mathbf{x}_K} \right| = \left| \det \prod_{k=1}^K \frac{f^{-1}_k}{\partial \mathbf{x}_k} \right| = \prod_{k=1}^K \left| \det \frac{f^{-1}_k}{\partial \mathbf{x}_k} \right|.\]Substituting this back into the objective function we obtain:

\[\max_{\theta} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \left[ \log p\left(f^{-1}_\theta(\mathbf{x}^{(i)})\right) + \sum_{k=1}^{K} \log\left|\det \frac{f^{-1}_k}{\partial \mathbf{x}_k} (\mathbf{x}^{(i)}) \right|\right]\]We can intepret the sum of log determinants in the objective as each “layer” of the flow receiving additional gradient information about the objective.

While we discussed that \(f_\theta\) is a sequence of transformations, we didn’t cover how to define those transformations. Research in normalizing flow methods typically consists of constructing transformations that are easily invertible and have simple and computable log determinants. The most well-known normalizing flow methods are NICE, RealNVP and Glow

For example, in the NICE paper, each transformation is a coupling layer that has a lower triangular Jacobian. The determinant of a triangular matrix is just the product of entries on the diagonal. The coupling layer transformation is quite simple. First we partition the input to layer \(K\) into two blocks \(\mathbf{x}_{K - 1} = [\mathbf{x}_{K - 1}^A, \mathbf{x}_{K - 1}^B]\). Then we compute the following:

\[\begin{align*} \mathbf{x}_{K}^A &= \mathbf{x}_{K - 1}^A \\ \mathbf{x}_{K}^B &= \mathbf{x}_{K - 1}^B + m_{\theta_K}(\mathbf{x}_{K - 1}^A), \end{align*}\]where \(m_\theta\) is some arbitrarly complex neural network at layer \(K\). Then we set \(\mathbf{x}_{K} = [\mathbf{x}_{K}^A, \mathbf{x}_{K}^B]\). In words, this transformation keeps the first block of the partition the same. The second block is updated/coupled with the first part based on some complicated function parameterized by a neural network. The inverse of this transformation can be obtain simply:

\[\begin{align*} \mathbf{x}_{K - 1}^A &= \mathbf{x}_{K}^A \\ \mathbf{x}_{K - 1}^B &= \mathbf{x}_{K}^B - m_{\theta_K}(\mathbf{x}_{K - 1}^A). \end{align*}\]The Jacobian of this transformation can be written as a lower triangular block matrix. We can see this by taking the derivative with respect to each part in the partitions. The following figure shows a visual depication of the transformation:

The next method we will cover is residual flows which will help us understand and motivate continuous normalizing flows.

Residual Flows

Many of the methods described above impose specific architectural constraints on the neural network to ensure that the transformation \(f_\theta\) is invertible. Furthermore, additional restrictions have to be placed in order to ensure the transformation has a sparse or structured Jacobian to make the log determinant easier to compute. Creating invertible neural network architectures with structured Jacobians is a difficult task that often leads to exotic designs, and in general, is a limiting approach to normalizing flows.

Residual flows make use of invertible-ResNets (i-ResNet) and compute an unbiased estimate of the log determinant

Recall that ResNets are a pretty simple architecture that consist of many residual blocks of the form:

\[\mathbf{x}_{t+1} = \mathbf{x_t} + g_{\theta_{t}}(\mathbf{x_t}).\]Simply transform the input \(\mathbf{x_t}\) via the neural network \(g_{\theta_{t}}\) at layer \(t\) and add it to itself. If we can find a way to make each layer invertible then the entire ResNet will be invertible. To understand how we can accomplish this, we first have to learn about the Banach fixed point theorem.

Suppose you have a contractive transformation \(T: \mathbb{R}^d \to \mathbb{R}^d\). Technically, \(T\) can map between any two general metric spaces but we will consider \(\mathbb{R}^d\) for simplicity. We say that the transformation \(T\) is contractive if there exists a constant \(K < 1\) such that for all \(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y} \in \mathbb{R}^d\),

\[\left\lVert T(\mathbf{x}) - T(\mathbf{y}) \right\rVert \leq K\left\lVert \mathbf{x} - \mathbf{y} \right\rVert.\]The Banach fixed point theorem states that there is a unique point \(\mathbf{x}\) such that \(T(\mathbf{x}) = \mathbf{x}\) i.e. \(\mathbf{x}\) is a fixed point that does not move under the transformation. In fact, we can compute \(\mathbf{x}\) using the following iterative procedure which provably converges. Select \(\mathbf{x}^{(0)} \in \mathbb{R}^d\) at random and then,

\[\mathbf{x}^{(n+1)} = T(\mathbf{x}^{(n)}).\]Intuitively, since \(T\) is contractive, the distances between images of the iterate \(\mathbf{x}^{(n)}\) and the fixed point \(\mathbf{x}\) under \(T\) will shrink. Since the distance is shrinking it must mean that the iterates are converging to the fixed point.

An equivalent way of stating that map \(T\) is contractive is declaring that \(T\) is \(L\)-Lipschitz continuous with constant \(L < 1\). To make a residual layer invertible, we are going to enforce that the neural network \(g_{\theta_t}\) is contractive i.e. it has \(L_t < 1\). Although this won’t provide us with an analytical form for the inverse, we can determine the inverse through an iterative routine. The proof of this is rather short. Suppose \(\mathbf{x}_{t+1} \in \mathbb{R}^d\) is arbitrary. We need to show that there exists a point \(\mathbf{x}_t\) such that \(\mathbf{x}_{t+1} = \mathbf{x}_t + g_{\theta_t}(\mathbf{x}_t)\). Let’s perform the following iterative routine with initial point \(\mathbf{y}^{(0)} = \mathbf{x}_{t+1}\):

\[\mathbf{y}^{(n+1)} = \mathbf{x}_{t+1} - g_{\theta_t}(\mathbf{y}^{(n)}).\]We are going to define transformation \(T_{\mathbf{x}_{t+1}}(\mathbf{w}) = \mathbf{x}_{t+1} - g_{\theta_t}(\mathbf{w})\). Notice that \(\mathbf{x}_{t+1}\) is a constant with respect to the transformation in \(\mathbf{w}\). Multiplying \(g_{\theta_t}\) by \(-1\) and adding a constant perserves the Lipschitz continuity and does not change the Lipschitz constant. Therefore, \(T_{\mathbf{x}_{t+1}}\) is also a contractive map. Therefore, there exists a point we will denote by \(\mathbf{x}_t\) that is a fixed point of the transformation and the above iterative routine is equivalent to the following:

\[\mathbf{y}^{(n+1)} = T_{\mathbf{x}_{t+1}}(\mathbf{y}^{(n)}).\]Therefore, the iterative subroutine will converge to fixed point \(\mathbf{x}_t\). Since \(\mathbf{x}_{t+1}\) was arbitrary and \(\mathbf{x_t}\) satisifies,

\[\mathbf{x}_t = \mathbf{x}_{t+1} - g_{\theta_t}(\mathbf{x}_t),\]the residual layer is invertible.

Now, how can we actually design a neural network \(g_{\theta_t}\) that will have a Lipschitz constant less than one? Fortunately, this does not require any complex architecture requirements. We can do this by using contractive activition functions such as \(\tanh\), ReLU and ELU and standard linear layers such as a feed-forward layer or convolutional layer. However, we must normalize the weight matrix of each layer, \(\mathbf{W}_i\) such that the spectral norm \(\left\lVert \mathbf{W}_i\right\rVert _2 \leq 1\). To do this, we compute an approximation of spectral norm of the unnormalized matrix and simply divide the unnormalized matrix by this approximation.

Once we have the invertible network, the next tricky part of residual flows is evaluating the log-determinant: \(\log\left\vert\det \frac{\partial f^{-1}_\theta}{\partial \mathbf{x}}\right\vert\) of the transformation. Interestingly, the log-determinant of each layer of the ResNet can be written as an infinite series of trace matrix powers:

\[\sum_{k=1}^{\infty} \frac{(-1)^{k+1}}{k} \text{tr}\left[\left(\frac{\partial g_{\theta_t}}{\partial \mathbf{x}}\right)^k\right].\]We can compute an approximation of this infinite series by truncating it to the first \(N\) terms where \(N\) is a hyperparameter. The trace of the matrix in each term can be estimated using the Hutchinson trace estimator. The Hutchinson trace estimator computes an unbiased estimate of the trace using matrix vector products. Specifically, to compute the trace of matrix \(\mathbf{A}\), we need a random vector \(\mathbf{v}_i\) such that \(\mathbb{E}[\mathbf{v}^{}_i\mathbf{v}^\top _i] = \mathbf{I}\). Then,

\[\text{tr}[\mathbf{A}] = \frac{1}{V} \sum_{i=1}^{V} \mathbf{v}_i^\top \mathbf{A} \mathbf{v}_i.\]In practice, we only use one sample to estimate the trace. Although the trace estimation is unbiased, since we always truncate the original infinite series at \(N\) terms, the overall estimate will be biased.

To make the estimator unbiased, we need to introduce some randomness into the truncation and take an expectation. Fortunately, we can use the “Russian roulette” estimator. The formula for the estimator is quite involved so we present a high-level intuition. The basic idea is that we always evaluate the first term and to determine whether we should evaluate the remaining terms we flip a coin that has probability \(p\) of coming up heads. If the remaining terms are evaluated then they are reweighted by \(\frac{1}{p}\) which results in an unbiased estimate. Futhermore, the estimate has probability \(1 - p\) of being evaluated in finite time (the case where we only evaluate the first term). Interesingly, we can obtain an estimator that is evaluated in finite time with probability one. We simply have to apply this process infinitely many times to the terms that have yet to be computed. Eventually, we are gauranteed to flip a tail and stop computing. Also, just like before we use the Hutchinson trace estimator to estimate the trace of the matrix in each term. Thus, we can compute this infinite series as:

\[\mathbb{E}_{n, \mathbf{v}}\left[\sum_{k=1}^{n} \frac{(-1)^{k+1}}{\mathbb{P}(N \geq k)} \mathbf{v}^\top\left[\left(\frac{\partial g_{\theta_t}}{\partial \mathbf{x}}\right)^k\right]\mathbf{v}\right],\]where \(n \sim p(N)\) for some distribution \(p\) and \(\mathbf{v} \sim \mathcal{N}(0,1)\).

Summary

To summarize, we have introduced normalizing flows, a class of generative models that learn an invertible transformation between a noise distribution \(p\) and a data distribution \(q\). We briefly covered some normalizing flow methods such as NICE that impose specific architectural constraints to ensure an invertible neural network and computable Jacobian. We discussed residual flows in detail which avoid exotic architecture design by using invertible ResNets. Relatively simple design choices can ensure that ResNets are invertible. Then we discussed how to compute an unbiased estimator of the Jacobian in the case of residual flows. Overall, normalizing flows are a powerful framework for generative modeling. Their main drawbacks include the limitation regarding architecture design and the high computational cost of the determinant of the Jacobian. In the next blog post, we will attempt to address these issues with continuous normalizing flows.