A Unified Framework for Diffusion Distillation

The explosive growth in one-step and few-step diffusion models has taken the field deep into the weeds of complex notations. In this blog, we cut through the confusion by proposing a coherent set of notations that reveal the connections among these methods.

Introduction

Diffusion and flow-based models

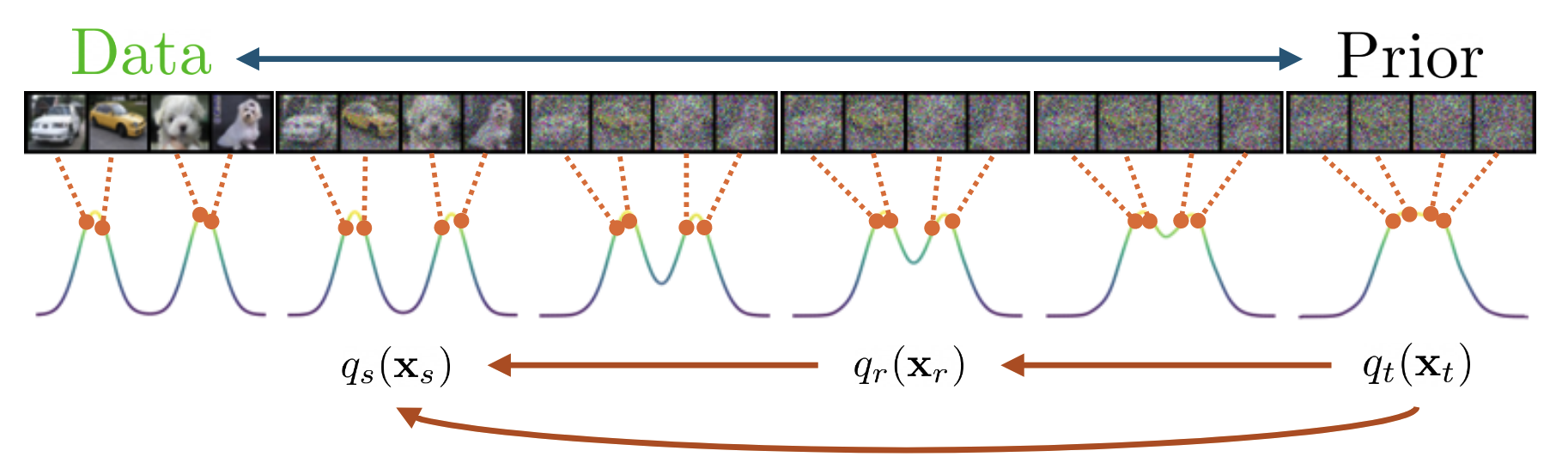

At its core, diffusion models (equivalently, flow matching models) operate by iteratively refining noisy data into high-quality outputs through a series of denoising steps. Similar to divide-and-conquer algorithms

This challenge has spurred research into acceleration strategies across multiple granular levels, including hardware optimization, mixed precision training

Distillation, in general, is a technique that transfers knowledge from a complex, high-performance model (the teacher) to a more efficient, customized model (the student). Recent distillation methods have achieved remarkable reductions in sampling steps, from hundreds to a few and even one step, while preserving the sample quality. This advancement paves the way for real-time applications and deployment in resource-constrained environments.

Notation at a Glance

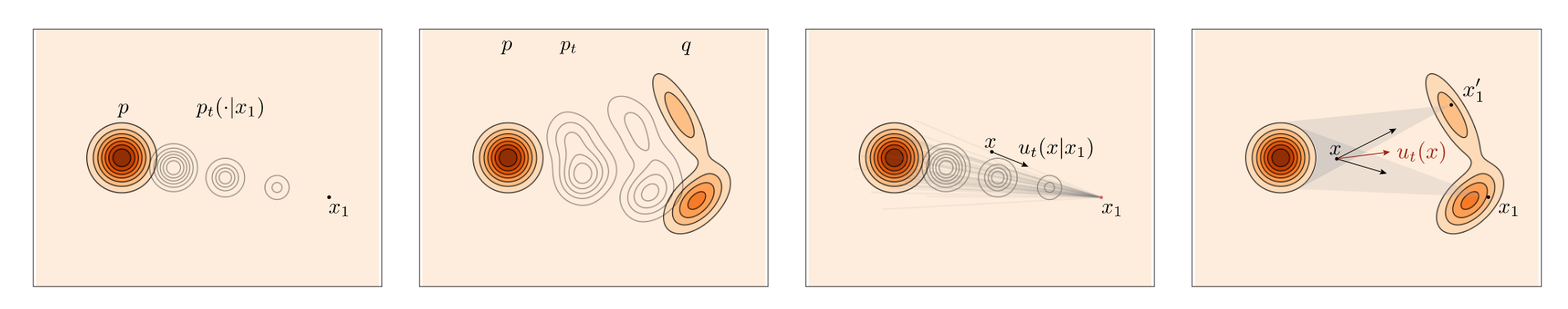

The modern approaches of generative modelling consist of picking some samples from a base distribution \(\mathbf{x}_{1} \sim p_{\text{noise}}\), typically an isotropic Gaussian, and learning a map such that \(\mathbf{x}_{0} \sim p_{\text{data}}\). The connection between these two distributions can be expressed by establishing an initial value problem controlled by the velocity field \(v(\mathbf{x}_{t}, t)\),

\[\require{physics} \begin{equation} \dv{\psi_t(\mathbf{x}_t)}{t}=v(\psi_t(\mathbf{x}_t), t),\quad\psi_0(\mathbf{x}_0)=\mathbf{x}_0,\quad \mathbf{x}_0\sim p_{\text{data}} \label{eq:1} \end{equation}\]where the flow \(\psi_t:\mathbb{R}^d\times[0,1]\to \mathbb{R}^d\) is a diffeomorphic map with \(\psi_t(\mathbf{x}_t)\) defined as the solution to the above ODE (\ref{eq:1}). If the flow satisfies the push-forward equation

Most of the conditional probability paths are designed as the differentiable interpolation between noise and data for simplicity, and we can express sampling from a marginal path \(\mathbf{x}_t = \alpha(t)\mathbf{x}_0 + \beta(t)\mathbf{x}_1\) where \(\alpha(t), \beta(t)\) are predefined schedules.

We provide some popular instances

| Method | Probability Path \(p_t\) | Vector Field \(u(\mathbf{x}_t, t\vert\mathbf{x}_0)\) |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian | \(\mathcal{N}(\alpha(t)\mathbf{x}_0,\beta^2(t)I_d)\) | \(\left(\dot{\alpha}_t - \frac{\dot{\beta}_t}{\beta_t}\alpha_t\right) \mathbf{x}_0 + \frac{\dot{\beta}_t}{\beta_t}\mathbf{x}_1\) |

| FM | \(\mathcal{N}(t\mathbf{x}_1, (1-t+\sigma t)^2I_d)\) | \(\frac{\mathbf{x}_1 - (1-\sigma)\mathbf{x}_t}{1-\sigma+\sigma t}\) |

| iCFM | \(\mathcal{N}( t\mathbf{x}_1 + (1-t)\mathbf{x}_0, \sigma^2I_d)\) | \(\mathbf{x}_1 - \mathbf{x}_0\) |

| OT-CFM | Same prob. path above with \(q(z) = \pi(\mathbf{x}_0, \mathbf{x}_1)\) | \(\mathbf{x}_1 - \mathbf{x}_0\) |

| VP-SI | \(\mathcal{N}( \cos(\pi t/2)\mathbf{x}_0 + \sin(\pi t/2)\mathbf{x}_1, \sigma^2I_d)\) | \(\frac{\pi}{2}(\cos(\pi t/2)\mathbf{x}_1 - \sin(\pi t/2)\mathbf{x}_0)\) |

The simplest form of conditional probability path is \(\mathbf{x}_t = (1-t)\mathbf{x}_0 + t\mathbf{x}_1\) with the corresponding default conditional velocity field OT target \(v(\mathbf{x}_t, t \vert \mathbf{x}_0)=\mathbb{E}[\dot{\mathbf{x}}_t\vert \mathbf{x}_0]=\mathbf{x}_1- \mathbf{x}_0.\)

Training: Since minimizing the conditional Flow Matching (FM) loss is equivalent to minimize the marginal FM loss

where \(w(t)\) is a reweighting function

Sampling: Solve the ODE \(\require{physics} \dv{\mathbf{x}_t}{t}=v_\theta(\mathbf{x}_t, t)\) from the initial condition \(\mathbf{x}_1\sim p_{\text{noise}}.\) Typically, an Euler solver or another high-order ODE solver is employed, taking a few hundred discrete steps through iterative refinements.

ODE Distillation methods

Before introducing ODE distillation methods, it is imperative to define a general continuous-time flow map \(f_{t\to s}(\mathbf{x}_t, t, s)\)

At its core, ODE distillation boils down to how to strategically construct the training objective of the flow map \(f_{t\to s}(\mathbf{x}_t, t, s)\) so that it can be efficiently evaluated during sampling. In addition, we need to orchestrate the schedule of \((t,s)\) pairs for better training dynamics.

In the context of distillation, the forward direction \(s<t\) is typically taken as the target. Yet, the other direction can also carry meaningful structure. Notice in DDIM

Our unified framework is closely resembles the flow map

MeanFlow

MeanFlow

where \(c_{\text{out}}(t,s)=s-t\). This is great since it attributes actual physical meaning to our flow map. In particular, \(f_{t\to s}(\mathbf{x}_t, t, s)\) represents the “displacement” from \(\mathbf{x}_t\) to \(\mathbf{x}_s\), while \(F_{t\to s}(\mathbf{x}_t, t, s)\) is the average velocity field pointing from \(\mathbf{x}_t\) to \(\mathbf{x}_s\).

We rearrange equation above.

\[\begin{equation} (t-s)F_{t\to s}(\mathbf{x}_t, t, s)=\int_s^t v(\mathbf{x}_\tau, \tau) d\tau \label{eq:2} \end{equation}\]Differentiating (\ref{eq:2}) both sides w.r.t. $t$ and considering the assumption that $s$ is independent of $t$, we obtain the MeanFlow identity

where we further compute the total derivative and derive the target \(F_{t\to s}^{\text{tgt}}(\mathbf{x}_t, t, s)\).

Training: Adapting to our flow map notation, the training objective turns to

\[\mathbb{E}_{\mathbf{x}_0, \mathbf{x}_1, t, s} \left[ w(t) \left\| F^\theta_{t\to s}(\mathbf{x}_t, t, s) - F_{t\to s}^{\text{tgt}}(\mathbf{x}_t, t, s | \mathbf{x}_0) \right\|_2^2 \right]\]where \(F_{t\to s}^{\text{tgt}}(\mathbf{x}_t, t, s\vert\mathbf{x}_0)=v - (t-s)(v\partial_{\mathbf{x}_t}F^{\theta^-}_{t\to s}(\mathbf{x}_t, t, s) + \partial_t F^{\theta^-}_{t\to s}(\mathbf{x}_t, t, s))\) and \(\theta^-\) means stopgrad(). Note stopgrad aims to avoid high order gradient computation. There are a couple of choices for \(v\), we can substitute it with \(F_{t\to t}(\mathbf{x}_t, t, t)\) or \(v(\mathbf{x}_t, t \vert \mathbf{x}_0)=\mathbf{x}_1- \mathbf{x}_0.\) Again, MeanFlow adopts the latter to reduce computation.

Full derivation of the target

Based on the MeanFlow identity, we can compute the target as follows: $$ \require{physics} \begin{align*} F_{t\to s}^{\text{tgt}}(\mathbf{x}_t, t, s\vert\mathbf{x}_0) &= \dv{\mathbf{x}_t}{t} - (t-s)\dv{F_{t\to s}(\mathbf{x}_t, t, s)}{t} \\ & = \dv{\mathbf{x}_t}{t} - (t-s)\left(\nabla_{\mathbf{x}_t} F_{t\to s}(\mathbf{x}_t, t, s) \dv{\mathbf{x}_t}{t} + \partial_t F_{t\to s}(\mathbf{x}_t, t, s) + \underbrace{\partial_s F_{t\to s}(\mathbf{x}_t, t, s) \dv{s}{t}}_{=0}\right) \\ & = v - (t-s)\left(v \nabla_{\mathbf{x}_t} F_{t\to s}(\mathbf{x}_t, t, s) + \partial_t F_{t\to s}(\mathbf{x}_t, t, s)\right). \\ \end{align*} $$ Note that in MeanFlow $$\require{physics}\dv{\mathbf{x}_t}{t} = v(\mathbf{x}_t, t\vert \mathbf{x}_0)$$ and $$\require{physics}\dv{s}{t}=0$$ since $s$ is independent of $t$.In practice, the total derivative of \(F_{t\to s}(\mathbf{x}_t, t, s)\) and the evaluation can be done in a single function call: f, dfdt=jvp(f_theta, (xt, s, t), (v, 0, 1)). Despite jvp operation only introduces one extra backward pass, it still incurs instability and slows down training. Moreover, the jvp operation is currently incompatible with the latest attention architecture. SplitMeanFlow

Loss type

Type (b) backward lossSampling: Either one-step or multi-step sampling can be performed. It is intuitive to obtain the following expression by the definition of average velocity field

\[\mathbf{x}_s = \mathbf{x}_t - (t-s)F^\theta_{t\to s}(\mathbf{x}_t, t, s).\]In particular, we achieve one-step inference by setting $t=1, s=0$ and sampling from \(\mathbf{x}_1\sim p_{\text{noise}}\).

Consistency Models

Essentially, consistency models (CMs)

Discretized CM

CMs are trained to have consistent outputs between adjacent timesteps along the ODE (\ref{eq:1}) trajectory. They can be trained from scratch by consistency training or distilled from given diffusion or flow models via consistency distillation like MeanFlow.

- Training: When expressed in our flow map notation, the objective becomes

where \(\theta^-\) denotes \(\text{stopgrad}(\theta)\), \(w(t)\) is a weighting function, \(\Delta t > 0\) is the distance between adjacent time steps, and $d(\cdot, \cdot)$ is a distance metric.

- Sampling: It is natural to conduct one-step sampling with CM

while multi-step sampling is also possible since we can compute the next noisy output \(\mathbf{x}_{t-\Delta t}\sim p_{t-\Delta t}(\cdot\vert \mathbf{x}_0)\) using the prescribed conditional probability path at our discretion. Discrete-time CMs depend heavily on the choice of \(\Delta t\) and often require carefully designed annealing schedules. To obtain the noisy sample \(\mathbf{x}_{t-\Delta t}\) at the previous step, one typically evolves backward \(\mathbf{x}_t\) by numerically solving the ODE (\ref{eq:1}), which can introduce additional discretization errors.

Continuous CM

When using \(d(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y}) = ||\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{y}||_2^2\) and taking the limit $\Delta t \to 0$, Song et al.

- Training: In our notation, the objective is

where \(\require{physics} \dv{f^{\theta^-}_{t\to 0}(\mathbf{x}_t, t,0)}{t} = \nabla_{\mathbf{x}_t} f^{\theta^-}_{t\to 0}(\mathbf{x}_t, t,0) \dv{\mathbf{x}_t}{t} + \partial_t f^{\theta^-}_{t\to 0}(\mathbf{x}_t, t,0)\) is the tangent of \(f^{\theta^-}_{t\to 0}\) at \((\mathbf{x}_t, t)\) along the trajectory of the ODE (\ref{eq:1}). Consistency Trajectory Models (CTMs)

- Sampling

Same as the Discretized Version. CTMs

Loss type

Type (b) backward loss, while CTMsFlow Anchor Consistency Model

Similar to MeanFlow preliminaries, Flow Anchor Consistency Model (FACM)

FACM imposes a consistency property which requires the total derivative of the consistency function to be zero

\[\require{physics} \dv{t}f^\theta_{t \to 0}(\mathbf{x}, t, 0) = 0.\]This is intuitive since every point on the same probability flow ODE (\ref{eq:1}) trajectory should be mapped to the same clean data point \(\mathbf{x}_0\).

By substituting the parameterization of FACM, we have

\[\require{physics} F^\theta_{t\to 0}(\mathbf{x}_t, t, 0)=v(\mathbf{x}_t, t)-t\dv{F^\theta_{t\to 0}(\mathbf{x}_t, t, 0)}{t}.\]Notice this is equivalent to MeanFlow where \(s=0\). This indicates CM objective directly forces the network \(F^\theta_{t\to 0}(\mathbf{x}_t, t, 0)\) to learn the properties of an average velocity field heading towards the data distribution, thus enabling the 1-step generation shortcut.

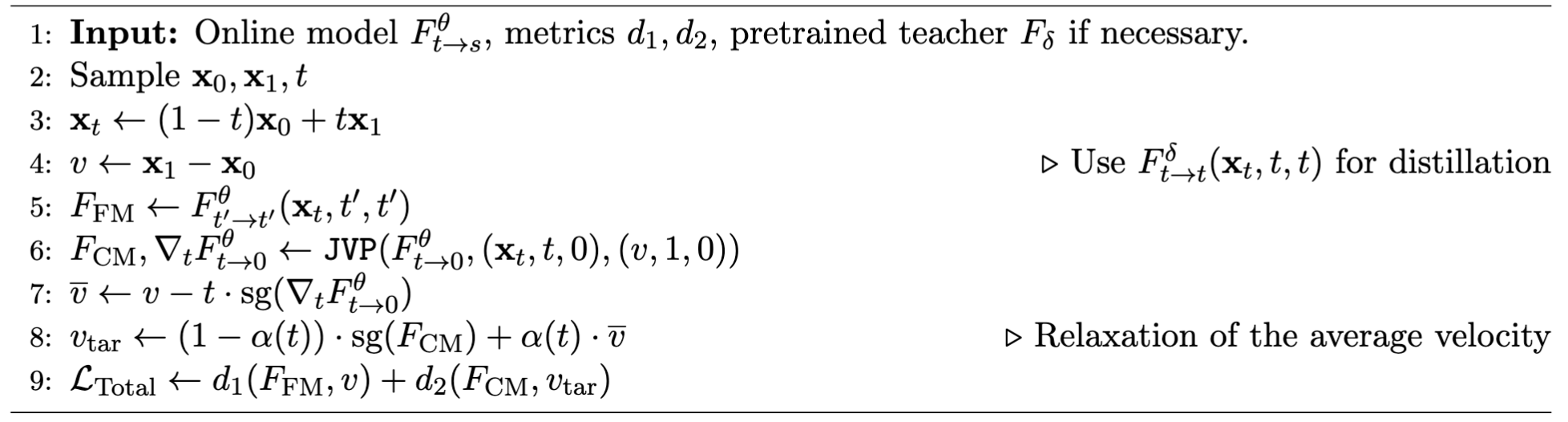

Training: FACM training algorithm equipped with our flow map notation. Notice that \(d_1, d_2\) are $\ell_2$ with cosine loss

Sampling: Same as CM.

Loss type

Type (b) backward lossAlign Your Flow

Our notation incorporates a small modification of the flow map introduced by Align Your Flow

Training: The first variant of the objective, called AYF-Eulerian Map Distillation, is compatible with both distillation and training from scratch.

\[\nabla_\theta \mathbb{E}_{\mathbf{x}_t, t, s}\left[w(t, s)\text{sign}(t - s) \cdot (f^\theta_{t \to s})^\top(\mathbf{x}_t, t, s) \cdot \frac{\text{d}f^{\theta^-}_{t\to s}(\mathbf{x}_t, t, s)}{\text{d}t}\right]\]It is intriguing that this objective reduces to the continuous CM objective when \(s=0\), while transforming to original FM objective when \(s\to t\)

Sampling: Same as CM. A combination of \(\gamma\)-sampling and classifier-free guidance.

The formulation of these objectives is majorly built on the Flow Map Matchingstopgrad operator to the loss to stabilize training and make the objective practical. In their appendix, they provide a detailed proof of why these objectives are equivalent to the objectives in Flow Map Matching

Loss type

Type (b) backward loss for AYF-EMD, type (a) forward loss for AYF-LMD.Connections

Now it is time to connect the dots with some previous existing methods. Let’s frame their objectives in our flow map notation and identify their loss types if possible.

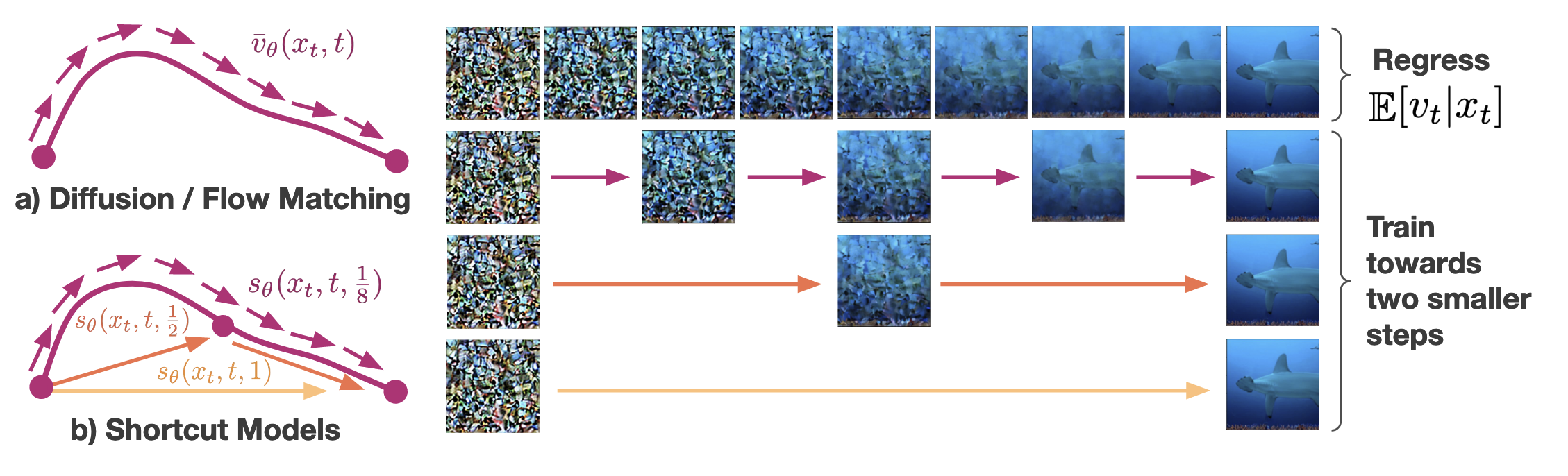

Shortcut Models

In essence, Shortcut Models

Training: In the training objective, we neglect the input arguments and focus on the core transition between time steps. Again, we elaborate it with our flow map notation.

\[\mathbb{E}_{\mathbf{x}_t, t, s}\left[\left\|F^\theta_{t\to t} - \dfrac{\text{d}\mathbf{x}_t}{\text{d}t}\right\|_2^2 + \left\|f^\theta_{t\to s} - f^{\theta^-}_{\frac{t+s}{2}\to s}\circ f^{\theta^-}_{t \to \frac{t+s}{2}}\right\|_2^2\right]\]where we adopt the same flow map conditions based on AYF.

Sampling: Same with MeanFlow yet with specific shortcut lengths.

Loss type

Type (c) tri-consistency lossReFlow

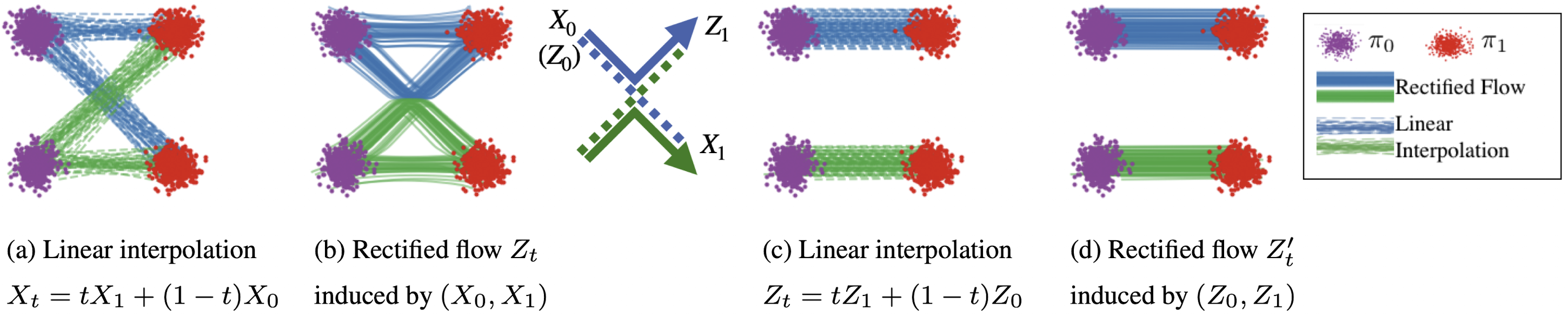

Unlike most ODE distillation methods that learn to jump from \(t\to s\) according to our defined flow map \(f_{t\to s}(\mathbf{x}_t, t, s)\), ReFlow

Training: Pair synthesized data from the pretrained model with the noise. Use this new coupling to train a student model with the standard FM objective.

Sampling: Same as FMs.

Inductive Moment Matching

This recent method

Training: In our flow map notation, the training objective becomes

\[\mathbb{E}_{\mathbf{x}_t, t, s} \left[ w(t,s) \text{MMD}^2\left(f_{t \to s}(\mathbf{x}_t, t,s), f_{r \to s}(\mathbf{x}_{r}, r,s)\right) \right]\]where \(w(t,s)\) is a weighting function.

Sampling: Same spirit as AYF.

Closing Thoughts

The concept of a flow map offers a capable and unifying notation for summarizing the diverse landscape of diffusion distillation methods. Beyond these ODE distillation methods, an intriguing family of approaches pursues a more direct goal: training a one-step generator from the ground up by directly matching the data distribution from the teacher model.

The core question is: how can we best leverage a pre-trained teacher model to train a student that approximates the data distribution \(p_{\text{data}}\) in a single shot? With access to the teacher’s flow, several compelling strategies emerge. It becomes possible to directly match the velocity fields, minimize the \(f\)-divergence between the student and teacher output distributions

This leads to distinct techniques in practice. For example, adversarial distillation

In our own work on human motion prediction

Diffusion distillation is a dynamic field brimming with potential. The journey from a hundred steps to a single step is not just a technical challenge but a gateway to real-time, efficient generative AI applications.